By Les Tan/Red Sports

Joseph Schooling sings the Singapore national anthem after winning the 100m butterfly gold at the 2016 Rio Olympics. (Photo © TSRIO2016 Reuters/Michael Dalder)

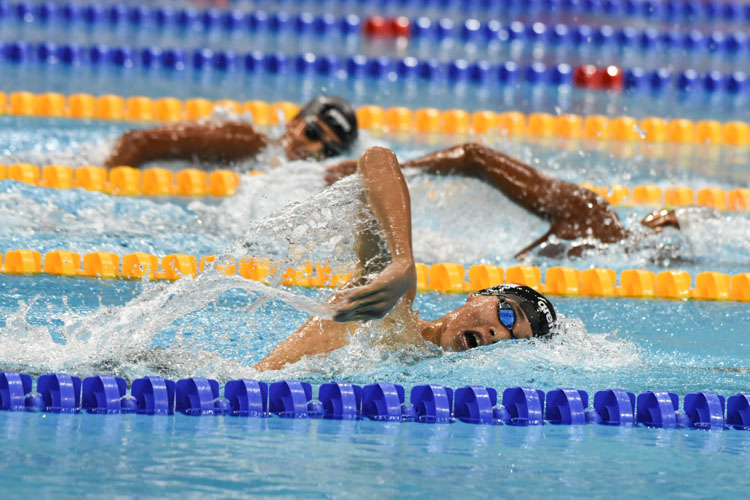

During the medal ceremony of Joseph Schooling’s astonishing win in the 2016 Rio Olympics 100m butterfly, I had missed it.

I was still blinking sleep out of my eyes, taking in the historic spectacle of a Singapore flag flying higher than the American one.

I felt compelled to stand in my own living room as my ears took in the Majulah Singapura coming from a ‘live’ televised Olympic event for the first time. The national anthem you usually hear on Channel 5 or 8 only bookends the broadcast day.

Later, with a second look at the photo above, I noticed it finally – Joseph had his hand over his heart while singing the national anthem. This echoes what the Americans do, a tradition they have had since 1942. Singaporeans sing the national anthem with their hands usually at their sides. Along with his American accent, it is a hint of where Joseph, now 21, has lived since he was 14.

This is not a criticism. Far from it. The six and a half years of living, studying, training, and competing in America have made him the All-American, and now Olympian, that he is, with a born-in-Singapore heartbeat.

When I saw that video of Joseph doing push-ups as a 14-year-old student of Anglo-Chinese School (Independent), it made me think of my teenage sons. How hard it must have been for his parents, May and Colin Schooling, to let their only son go away at 14, and to see him only a few times a year. And how hard it must have been for Joseph himself to leave at such a young age, to lose friends, and try to find new ones, especially as a teenager.

But the Schooling family made that decision, they took the plunge, they sacrificed. Joseph, who must have passed his 10,000 hours of practise some time back, translated those boring hours into an electrifying 50.39-second Olympic record. The credit is theirs.

For some of those who first came across the name of Schooling, the inevitable question arose. Is he Singaporean? As a third-generation Singaporean, he does not even have to answer that.

Yes, Singaporeans are more familiar with family names like Tan and Chan, Prakash and Elangovan, Ahmad and Mutalib, Pereira and Fernandez. However, in the past decade I have also come across Bardelli and Bennett, Hodge and Duric, Wilkinson and Susilo, Fahrudin and Feng – all Singaporeans.

So what is a Singaporean?

Race and ethnicity are primal, no doubt. But to just stay within those confines may lead us down alleys from which we might never emerge.

The first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, said in 1965, “We are going to have a multi-racial nation in Singapore. This is not a Malay nation, not a Chinese nation, not an Indian nation. Everybody will have a place in Singapore … We unite regardless of race, language, religion or culture.”

In this world of ours, broken by race, language, or religion, Singapore is a statistical and historical astonishment. We have kept astonishing others – and maybe even ourselves – in part because we have held our doors open.

But like the automatic sliding doors at shopping malls and office buildings, they remain closed when no one approaches. And when the crowd stops coming through those doors, the livelihoods of those inside shrivel and die.

We are alive because we have been open to others. We are alive also because others have been open to us. When doors closed shut to us in our region, we welcomed the world. And that has given us a life.

Singapore, an island nation, merely 51 years, is still just an idea with few precedents. If she washes away tomorrow with the tide of history, academics will just say, “No surprise there.”

And because it is just an idea, and so fragile, we repeat it every year – ad nauseum for some.

However, when someone like Joseph Schooling shows up and wins Olympic gold, this idea takes flesh and we understand again.

Because with a name like Schooling, it reminds us that his ancestors came to Singapore and made it home; and with his journey to America, it reminds us that if we are to not just survive, but to excel, we have to make the world our home too.

Singapore, as an idea, is as open or as closed as the mind that holds it.

The journey of one Joseph Isaac Schooling, born in Singapore on June 16, 1995, to proud parents Colin and May, reminds us to keep the Singapore idea alive, and our minds, and especially our hearts, open.

N.B. This article was also posted in its entirety on the Red Sports Facebook page on August 14, 2016. As of Aug 27, 2016, it has received over 2,100 ‘likes’, 780 ‘shares’, and 66 comments. The article has reached 219,093 people according to the Facebook analytics.

Spot on Leslie. Singapore, as an idea, is as open or as closed as the mind that holds it. Dead on.