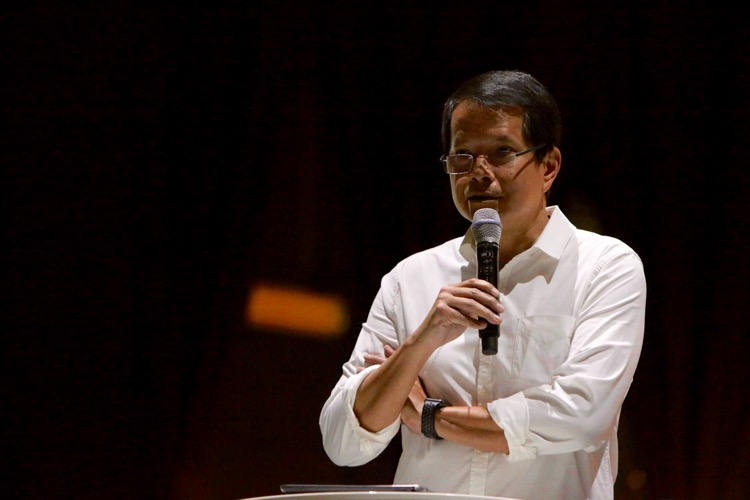

Professor Dr. Arne Güllich speaking at the 2016 Youth Athlete Development Conference. He is the Head of Department of Sport Science and Director of the Institute of Applied Sport Science, Kaiserslautern University of Technology. The National Youth Sports Institute organised the conference which was attended by 200 people. (Photo 1 © Les Tan/Red Sports)

Singapore Sports Hub, Tuesday, November 8, 2016 — “Junior success is a poor indicator of long-term senior success. Their success at the age of 10 had a zero correlation with their success as a senior. Same was true with their success at 11-14, 15-18. We have a zero correlation.”

Professor Dr. Arne Güllich delivered this startling statement at the 2016 Youth Athlete Development Conference.

Professor Güllich, who is the Head of Department of Sport Science and Director of the Institute of Applied Sport Science, Kaiserslautern University of Technology, was sharing research findings to 200 physical education teachers, coaches, and sports administrators at the inaugural conference.

“That means, those who were better at a young age were not those who were better at an older age. This also applies to different types of sports – CGS sports (where performances are measured in centimetres, grams, seconds), games sports, combat sports, artistic composition sports. The results are all the same across all different types of sports,” he added.

In the case of combat sports, he found a negative correlation.

“Those who were top athletes at senior level (in combat sports), were those who were behind at age 11 or 10.”

Even in cases where the talent is correctly identified at a young age, the chances of the athlete becoming world class is low.

“We assume one out of 1,000 youngsters becomes an international, senior top athlete, which is quite realistic. Further, we assume we have 70 percent correct assignment by our talent identification tests. The result is … the probability of a positively identified talent to actually become an international senior athlete is 0.2 percent,” said Professor Güllich.

Professor Güllich gave an example from the German football TDP (talent development programme) system to show that the most successful seniors were not selected particularly early.

“Of those who were recruited at an age of under 11 or under 13, at the age of under 19, only 9 percent are left. On the other hand, those who made it to the national A team of Germany, those we see in the World Cup for example, were being built up gradually across all age stages,” he said.

“The population of senior top athletes emerges in the course of repeated selection, de-selection, and replacements across all age stages rather than developing from those early selected,” he added.

In fact, what stood out from his research was that world-class athletes did not just focus on their sport from a young age, but played more than one sport.

His research has shown that German Olympic medalists played two or three other sports at a high level before focusing on their main sport at 20.

“The world-class athlete differs from those who made it only to national class, not by having engaged in more sports specific training in their main sport, this was indifferent, or they even trained less at a young age at their later main sport, but consistently, they engaged in more activity in other sports,” said Professor Güllich.

He also found that early specialisation may lead to success at a youth level, but not necessarily at a world level.

“Consistently, those who were recruited into the system earlier, started specialising significantly earlier. As a result, looking at where they got to in the long term, those recruited earlier were more successful at a youth age, but they were under-represented in terms of senior world class (top ten worldwide),” said Professor Güllich.

Professor Dr. Arne Güllich speaking at a breakout session during the 2016 Youth Athlete Development Conference. (Photo 2 © Les Tan/Red Sports)

___________________

Below are selected transcribed quotes from the presentation by Professor Dr. Arne Güllich at the 2016 Youth Athlete Development Conference. You can also watch the video of his entire presentation below.

TID tests can distinguish between future higher and lower performers

“There are some quite promising studies that reach up to 70% correct assignments to groups of higher performers or lower performers a couple of years later. The problem is not test accuracy. The main problem is the base rate.

“Ackerman illustrated the case with a simple calculation. We assume one out of 1000 youngsters becomes an international, senior top athlete, which is quite realistic. Further, we assume we have 70% correct assignment by our talent identification tests. The result is, even with a very high correct assignment of 70%, which is at the upper margin of what we have found in empirical studies, the probability of a positively identified talent to actually become an international senior athlete is 0.2%.

“Even if we raise the predictive accuracy of our tests to an incredible 90%, this rate would only rise to 0.9% of correct identification. This is quite consistent with what we find in empirical studies at around or up to 2% of those identified as talented at an early age who actually become an internationally successful athlete.

“The problem of talent identification is not in the sophistication of the tests that we apply, the problem is in the nature of the subject. So whatever we do to improve our tests and raise their reliability, validity, and predictive accuracy, it is very improbable that we will exceed values such as these.”

Does early involvement in TDP correlate with later senior success?

Successful senior athletes in Germany were selected later

“There were athletes who did not exceed initial D squad (regional junior squad), they were first recruited into the system at 15 years. The C squad (the national junior squad) were first recruited at the age of 17. Those who made it to senior world class (A squad) were first recruited at 19 years. So the more successful at the senior level, the later was the recruitment into the talent development system.”

Does early TIP/TDP preferentially select and facilitate developmental participation patterns that facilitate long-term development of outstanding senior success?

“This is a review of a number of studies that all had one thing in common – they compared different groups of athletes who attained higher or lower success – and they compared them with regards to the activities they had engaged in. This is a summary of whether the volume of their juvenile engagement in their main sport or in other sports correlated with later senior success. And we divide between youth and adult success.

“What these results say is that to attain higher youth success, it is beneficial to increase the volume of sports specific practise in the main sport while engagement in other sports is either indifferent or even inhibitory to rapid juvenile success.

“But when we have a look at the juvenile activities with regard to long-term, international senior success, it is just the opposite. The world-class athlete differs from those who made it only to national class, not by having engaged in more sports specific training in their main sport, this was indifferent, or they even trained less at a young age at their later main sport, but consistently, they engaged in more activity in other sports.”

Early TID and TDP boost early specialisation

“Consistently, those who were recruited into the system earlier, started specialising significantly earlier. As a result, looking at where they got to in the long term, those recruited earlier were more successful at a youth age, but they were under-represented in terms of senior world class (top ten worldwide).

“In addition to that, once recruited into the system, during the next three years, we followed them up, those having been recruited into the system, increased their specific practise in their main sport by 95% more than their peers who had not been recruited.”

Does the population of senior elite athletes a) develop from those selected early and their long-term nurturing, or rather b) emerge via the course of repeated selection, de-selection, and replacements through the consecutive age stages?

TDPs display high annual athlete turnover

“We find that the annual athlete turnover (in the German system) is around 20 to 30% in these locally based programmes, and at national squad level, is even above 40%. This signifies that after five years, only less than 40% of the initial athletes are still within the system, or in the case of national junior squads, less than 10%.”

Most early selected youngsters do not become successful seniors. Most successful seniors were not selected particularly early.

Example from the German football TDP system

“Of those who were recruited at an age of under 11 or under 13, at the age of under 19, only 9% are left. On the other hand, those who made it to the national A team of Germany, those we see in the World Cup for example, were being built up gradually across all age stages.”

Implications

“We can see that sports system where competitive sports is cultivated massively, future top athletes can actually not be predicted reliably by way of young age TID.”

“Particularly early TDP is neither necessary nor beneficial, but rather correlates negatively with long term senior success.”

“Early TID/TDP preferentially selects and also reinforces early specialisation and intensification of specific practice.”

“The population of the early selected and the successful seniors are not identical and are widely disparate populations. The population of senior top athletes emerges in the course of repeated selection, de-selection, and replacements across all age stages rather than developing from those early selected.”

Questions for practitioners and governing bodies

1. At what age to start TID and TDP?

2. What numbers of athletes to involve at what age?

3. By what criteria to select ‘talents’?

4. What conditions to provide and what interventions to apply to the selected? How intensively to nurture them?

More photos next page

[…] Junior success is a poor indicator of long-term senior success – Professor Dr. Arne Güllich […]

[…] You can read further about his presentation to 2016 Youth Athlete Development Conference here. […]

[…] “Junior success is a poor indicator of long-term senior success” are the research findings of Dr. Arne Güllich on investigating the efficacy of a number of early TID programmes. […]

[…] all the evidence tends to suggest the opposite. A recent article from a talk by Professor Gullich https://www.redsports.sg/2016/12/03/youth-athlete-development-conference/ suggests that even early success has zero predictive ability of long term […]

[…] Read the entire article here. […]

[…] Junior success is a poor indicator of long-term senior success – Professor Dr. Arne Güllich […]