Story by REDintern Joy Poon and Samantha Yom/Red Sports.

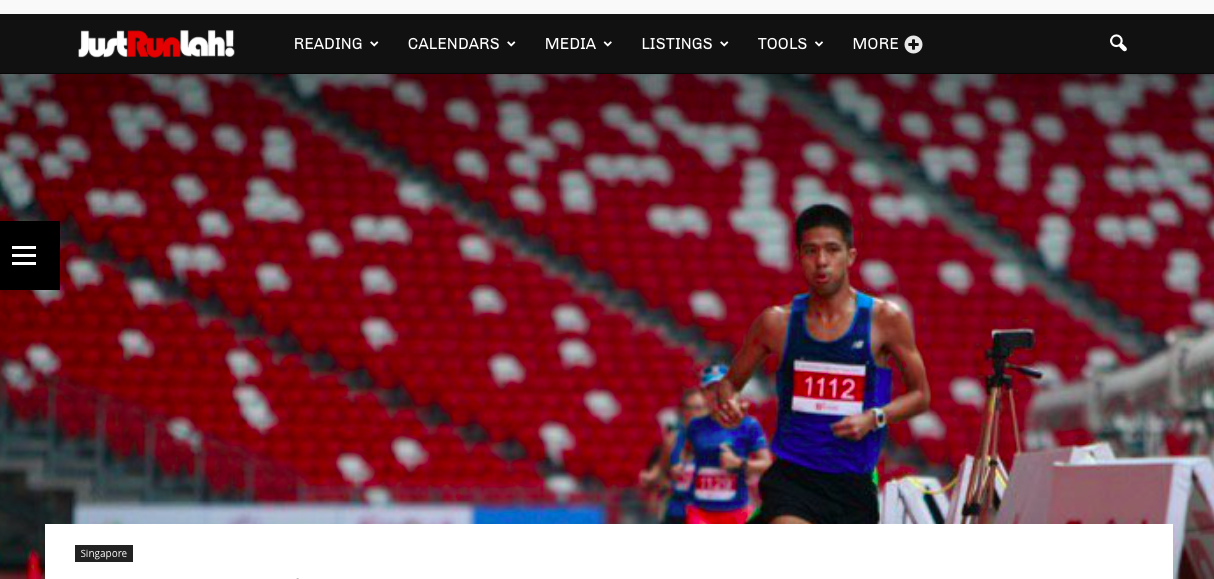

Jordan Chia in action at the Track & Field National School Games. (Photo 1 © Lim Yong Teck/Red Sports)

We all love a good tale of David and Goliath and the Norwegians have presented us with just that. Norway has a population smaller than Singapore’s and a sports budget a fraction of their closest rivals. Nevertheless, that did not stop them from surpassing the current record – set by the US – for the most medals won at a single Winter Olympics.

Their impressive haul of 39 medals at the Pyeongchang Winter Games not only put them at the top of the table, but a good eight medals clear of runner-up Germany.

Certainly, they must be doing something right. Being blessed with heavy snowfall and having a history of skiing excellence to boast does not automatically guarantee you a spot atop the all-time Winter Olympics medal standings. So what exactly is their secret to winter sport dominance?

It seems to lie in their emphasis that sport should be for fun rather than competition, especially for children.

This is why you will not find rankings for children under the age of 11. Children can compete before that age, but they are never ranked. And should competition organisers choose to give out prizes, every child goes home with one.

“We want them to play. We want them to develop, and be focused on social skills. They learn a lot from sports. They learn a lot from playing. They learn a lot from not being anxious. They learn a lot from not being counted. They learn a lot from not being judged. And they feel better. And they tend to stay on for longer,” said Tore Ovrebo, director of elite sport for the Olympiatoppen (the organisation responsible for training Olympic athletes), in an interview with Time on February 25, 2018.

This is a far cry from what we see in our local sports scene, one that struggles with participation and retaining youth talent. More often than not, we blame it on the competitiveness and the pressure to perform from young.

Yet, we all want to hear Majulah Singapura ring out in an Olympic venue once again. Perhaps, we could have the Norwegians remind us about what truly matters in sport.

Norway’s golden approach

“I probably did four to five sports… I am very lucky to have gotten the chance to do several sports (when I was young), so I could and still can choose a combination (of these sports), and continue to do them for the rest of my life,” Jannicke Stalstrom noted.

Jannicke is a three-time Olympian from Norway. She competed in sailing, but just like many other Norwegians, she did a variety of sports as a child – something pretty much unheard of here in Singapore.

She added: “I think it is important to have a repertoire of more than one sport, so that you can develop the capacity and ability to use your body and be able to take part in several sports in your lifetime.”

All over the world, the age of children specialising in a particular sport has only gotten younger. However, Norway has stood firm in their belief that sport ought to be a platform to learn new skills and values, and should eventually become a way of life.

So their children take part in sport sans the pressure, anxiety and expectations. They still compete though, just that results are never the focus. Their scores are not kept, their performance not measured in numbers. Instead, skills development and mastery are emphasised.

Children are also disallowed from participating in championships such as European and World Championships (or its equivalent) until the year they turn 13, though they can start competing against their peers from the Nordic countries two years earlier.

These rules, among others, align with the Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports’ (NIF) Development Plan, which clearly spells out the objectives for the various age groups.

For instance, at six years, the focus is on deliberate play and the strengthening of basic movement skills. Between seven and nine, the aim is to let children explore various physical activities and develop a good foundation in a range of skills, while the intensity of these activities are scaled up to ensure solid basic skills for kids ages 10 to 12.

Ultimately, at the heart of these regulations is the desire to create a positive experience for children as they discover and take part in various sports, to experience sport for what it truly is – fun, rewarding and inspiring.

And according to them, that is what keeps people in sport.

The Singapore situation

When Jordan Chia, an ASEAN School Games Shot Put Gold medalist, participated in his first International Little Athletics Championship five years ago, the then 14-year-old broke a championship record, set a new national under-15 mark and bagged two Gold medals.

He found himself well ahead of his fellow Malaysian and Australian competitors (the Championship is an annual tri-nation meet), but he noticed that the Australians were competing in cross-disciplinary events, across the throw, jump and sprint disciplines. This was a stark contrast to the Singaporean athletes who were highly-skilled for their age, yet already specialised in their respective disciplines.

Primary school students competing at their annual National School Games. (Photo 2 © Lai Jun Wei)

“In Singapore, the idea of competitive sports is usually so ingrained in us from the get go. When we pick up the sport at the tender age of 9 or 10, some even earlier than that, we are already being pushed to train to the extreme, to achieve the fastest and best results possible at that time,” noted Jordan.

In fact, for a good number of Singaporean children, their experience with sport is almost similar to academic-based tuition classes. Parents sending their children for intensive swimming lessons or one-to-one tennis coaching is not an uncommon sight. Meanwhile, after-school sports Co-Curricular Activities (CCAs) often centre around deliberate practice rather than fun, though they are not mutually exclusive.

The highly competitive Direct School Admission exercise, which allows Primary 6 students to gain direct entry into secondary schools via their sporting talents and achievements, is partly responsible for the tendency to specialise early in a sport too.

It feels as though children are conditioned to focus on excellence, instead of the joy of playing sport. They end up concentrating on a certain sport from young – or are ultimately compelled to do so when they get older. The result is a lack of exposure to a variety of sports that can potentially turn them into more versatile athletes.

Early specialisation and competition: Is it all that bad?

Early specialisation certainly has its drawbacks, as national shooter Martina Lindsay Veloso would know.

“I was brought up doing sports competitively and felt that I frequently missed out on the fun things people do around that age,” admitted Martina, who recently bagged two Golds at the Commonwealth Games.

Martina is one of the fortunate ones that went on to thrive in their sport. However, there are many young athletes who turn away from sport as the psychological stress, which comes with competition, gets too overwhelming.

“If there is an external pressure to win at a young age then the self-worth of the youth athlete is linked to this outcome. If there is an internal focus on mastery, then this self-worth is linked to how much the youth athlete improves, which is more sustainable in the long term,” shared Matthew Wylde, Head of Performance Analytics at the National Youth Sports Institute (NYSI).

Tan Weixuan, a national fencer, was also quick to point out that the focus on results may prevent these athletes from gaining true sporting experience – something that he believes is far more important than collecting ranking points, especially at a young age.

Children who specialise in a sport from young face the risk of injury and burn-out as well.

Matthew added: “There is a growing body of evidence that shows that high training loads in a single sport at a young age are linked to overuse injuries. If you are constantly injured you cannot train and are less likely to continue with your sport.”

All the same, early specialisation has its advantages as well. For one, the rigour of competitive sport she experienced as a child played a major role in moulding Martina to become the athlete she is today.

“I have no regrets (starting competitive sport early) as I have learnt values such as self-discipline and resilience. These are some things that sport teaches even at a very young age,” she shared.

Furthermore, an early head start is almost necessary for some sports, considering the need to master certain movements from young.

According to research literature, there is a “golden age” – from age seven to 12 – for motor development, and this is the critical period to teach body movements, says Jannicke, who went on to cite swimming and gymnastics as an example.

Sports like these require commitment from young to master technique, and so it is unlikely that we will be seeing Norwegian gymnasts dominating the Olympic podium anytime soon.

“We do realise that Norway will never be able to compete with the world in some sports, such as Gymnastics. With our sport policy for the youth, we simply cannot match the rest of the world,” Jannicke acknowledged.

Moving forward – and away from the competition

There is definitely a need to look at sport in its broader sense, past the medals and championship titles. It ought to become a way of life for our children. And a joy. However, in order to achieve this, we need to provide them with the opportunity to discover all kinds of sport and to adjust our expectations.

Perhaps, we can start by looking at how we can keep sport accessible. It is more than a matter of conveniently-located sporting facilities. It is also about making sure that the growing intensity of competition does not push people away from a sport.

Norway does a good job in that aspect. For instance, weight restrictions on race bikes were recently introduced to ensure that recreational cyclists, who usually could not afford the expensive high-performance bikes elite athletes could, would still be able to participate in competitions.

Singapore has been looking to make sport more accessible too, with the the Junior Sports Academy (JSA) Programme.

The programme is an effort by our Ministry of Education (MOE) and NYSI to make sure that a broad-based exposure to sport is offered to physically talented primary school students, regardless of their background. The two-year programme, which was revised in 2015 to emphasise broad-based development, gives some 900 students the opportunity to play a different sport every semester during weekly sessions conducted all over the island.

But would Norway’s unique approach to sport for children work in Singapore?

Matthew suggests looking at the response to the recent changes in the competition structure of the National School Games’ Junior Division, which made it more appropriate for the developmental progression and age of the child, as an indicator.

“The vast majority of people appear to be supportive and I think intuitively people know that putting too much emphasis on winning at Primary School level is not a good thing. However, there is still a vocal minority against the proposed changes, who feel that this would in some way make our children ‘soft’.”

Or maybe a shift in mindset is all that is needed to take the pressure off our young athletes and to get them involved in a wider range of sports.

Jannicke believes it’s a matter of redefining excellence.

“I definitely think that it’s the grown ups who are defining excellence today. For kids, it can be the privilege of wearing the club shirt, making that gybe (a sailing manoeuvre), mastering something on the field or just being a really good friend and part of a sports group that feels like excellence to them. Excellence is not limited to winning the race, but can be perceived as simply making it to the start line.”

I enjoyed this article very much, because going up I played multiple sports, track and field, volleyball, basketball, skiing, cross country running. I was good at many sports, but never the best. It taught me to have a growth mindset, to never give up and not be afraid to try new sports. I learned to telemark ski at 23 and was on the National B team at 28.

I am a physical educator in a small town, over the last 8 years elementary school sports have been on the decline due to structured after school activities for students. Schools can no longer field volleyball or basketball teams our focus has become individualized sports for grade 3-6, with participation waining in grade 5.

[…] Let the children play – Norway’s golden approach reminds us of what matters in sport […]

Very interesting article. I coach girls youth soccer and strength training in the United States. I have found a similar strategy to be successful with my programs. Our goals on the pitch and in the fitness centers are about personal development, enjoyment of the process and focusing on elements we can control. It has very much helped with team retention rates and the young athletes continue to make great progress.

Very interesting article. I coach girls youth soccer and strength training in the United States. I have found a similar strategy to be successful with my programs. Our goals on the pitch and in the fitness centers are about personal development, enjoyment of the process and focusing on elements we can control. It has very much helped with team retention rates and the young athletes continue to make great progress.